“Package My Opinion”

An interview by Brigitta Iványi

BI How have you divided up the material presented in this book?

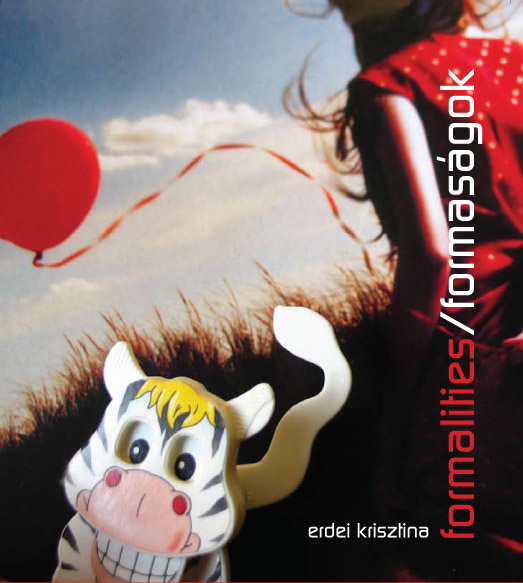

KE The first part features the present characteristics of “everyday geography” from the perspective of the new generation. The second part describes rural thought and life, the mood tangible in a hobby garden. Elaborating on the process how the objects of Post-socialist countries are covered by colorful plastic scenery coming from the West (but manufactured in the East), the third part is about “plastic culture”. So this last series focuses on objects, while the first and the second on people in the towns and the countryside, respectively.

Beyond these thematic clues, the structural markers unify the whole of the material. It is often said that my photos resemble amateur shots, and I did work in a lab producing photos developed in mass quantities, so I was heavily affected by the directness of the photos seen there. However, it is often complicated to shoot a photo exactly in a way that it shows every single detail as I wish. Digital technology helps in this, and gives a chance to experiment using immediate feedback. If I fancy a situation I take photos until I am satisfied. Sometimes I start missing something from the frame afterwards. Something that belonged there, but was not present at all or not how I wanted. In these cases I create a photo montage of the separate details manually. But in most cases the pictures are created by the joint workings of contingency and routine. I am a photographer in a sense that I first collect empirical experience and information through taking photos, and then I compile the pictures that are most appropriate to express what I want to show. The results are funny and esthetical according to a lot of people, but I also hope there is something else beneath the packaging, something not exactly sad, but rather serious.

BI If one wants to document the lives of people living in a certain location and time through observing elementary weekday activities and environments, this project can be interpreted as sociological research as well. In this sense your work can be perceived as data mining.

KE Sure, but it might not be that systematic. This is not like social studies, because it does not rely on a questionnaire, and it does not collect information with a pre-defined scope. This project is based on a different method. I do not have a hypothesis to start out from, I have an urge to show certain things, and as I take more pictures they add up to a vision, not a case study. Experiments always attempt at being objective, my work on the other hand does not. What I do is a kind of subjective documentarism. My photos move away from earlier documentarist works in their structural aspects. Since this is an authentic work and describes reality in a subjective way, I consider it documentary, but it is not objective in the same sense as scientific experiments.

BI You are saying that your work cannot be called systematic in the same way as scientific research. What do you call systematic?

KE I have not ever felt at home in scientific discourse. I did study philosophy at the university, but philosophy is exactly about whether or how it is possible to transgress the limits of science and humanities. What I am interested in is not really factual or rationally comprehensible. Taking photos is improvisation. I can “package” my opinion in the capturing of a momentary view, and describe the correct narrative through highlighting details, taking seriously what is written on their faces.

BI When you take photos you say you want to reveal reality, and while you collect these slices of life, each of them turns into a picture referring to something beyond itself. Do you think this works with any photo of yours in itself, or is it only possible to make visible the substantial pattern beneath the pictures in a series?

KE I think it works on any one photo, as well. Each picture has its own little punch line. For instance the one in which a hen is being slaughtered the blood spills out in the shape of a bird, as if it would be its soul… But I always like showing them in quantities. If you look at a bunch of picture one after the other, what they are about seems more true, and the emphases may shift, too. It is like “animating” the narratives – not only with the characters, but it is also possible to provide things with souls.

BI You take photos at a large variety of places, both geographically and socially. Does the constant change of locations increase the contingency of your work or is it all the same where you take photos, since you will capture highly similar phenomena anywhere?

KE Both are true. In the beginning it was accidental where I took photos, but recently I became rather conscious in picking places. Due to globalization, some topics are accessible everywhere. It is also interesting to take a look at how certain visual elements add up at various places. This book is not the end of something; it would be nice to go on looking for things at more remote places, where I have not been.

BI Do you pick the right place and time in search of change or transition of a particular way of life? Do you look for the grotesque in environments and behaviors that accompany certain ways of life, and become parodies of them?

KE Absolutely. As for the topics, I try to do so in my work. Where things are heading, the power of routines, unperceivable traditions governing one’s actions – these things are pretty important for me. New generations always grow sensitive to and react on superficial routines.

BI What you said, the substantial beyond the visible – this may either be metaphysical references or sociological statements about the state of society. What is the thing not identical with the object represented in the photo, the thing the picture refers to?

KE It has already been said about my work and especially this compilation that it is philosophical and raises abstract associations. My photos primarily show sights, and I cannot guess the associations you arrive at, starting out from them. It is easier for me to talk about them one by one, and try to explain how each of them relates to our environment. For instance, in the one in which two ladies are chatting in a tram stop there is an advertisement in the background in which a row of houses can be seen. It could also be a row of real houses, because the perspective is the same, but in that neighborhood there are no new houses except those on posters. Our environment is full of advertisements, illustrations which all mean something, but we cannot take these sensational sights seriously, and it is easier to walk past them without a glance. Visuals and moods are created through these, but in some contexts they become controversial at the same time.

BI Most of your photos question the context of things not fitting their environment, and imply how they characterize the people who put them where they are, and the others who live around them.

KE I think these things have even started to fit their environment. If one comes across two plastic giraffes on a European beach, for example, one will not even notice, because it is absolutely natural that our children play with objects like this.

BI Have you already started taking photos while studying philosophy?

KE I was interested in black and white exclusively at the university, but this is typical with learners of photography. I have not started investing this much energy into photo. The pictures included in this book were taken in the period from 2003 to 2007.

BI Photo became more important in your life after university. There is an intellectual position when you participate in culture through exiting it.

KE I guess philosophy is like this, while photo is the exact opposite. I was really interested in philosophy, but then I got scared that I could not do it at a level so high that I would actually create something. I had an intention to express myself, and I had to find a field in which I could make this happen.

BI I feel the methods through which philosophy can observe the world and make statements about it, are close to you, but you prefer a version of this which incorporates more intuition and contingency, and moves closer to everyday reality…

KE …or, rather, to people, because I like to come together with people and participate in community activities. I think people are really interesting, all of them. My personality is pretty quick, flexible, and dynamic, and photo suits these features. I used to experiment with drawing and painting, too, but I stuck to photo as it is faster. Its pace was way handier for me than that of philosophy.

BI It is very telling that you shifted the comparison in this direction. I assumed that you are an observer both as philosopher and photo artist.

KE This is exactly true for photo journalism. But I do not perceive myself as an outsider while at work. I am present in the situation, part of it, and experiencing it. I do not have topics like: pick a fair and show how it looks. My photos are either created by the fact that I end up at a place and capture a situation there or I am curious about something and I go there to take photos. Seventy percent of the pictures are found moments, while the other thirty percent results from a previously arranged experiment. With this latter type I make arrangements, but not a rigidly as with a studio photo, because I always give a chance to accident, and I am curious about what will finally turn up. I prefer taking photos of events, movements, actions. So I feel I am actually part of the narrative, not an outsider. Still, there is an outsider component, too, because with some photos I am there as an observer. That is why this book is not a diary.

BI A number of your pictures relates to gender issues in a way, and several texts discussing your work talk about the presence of this angle. How would you situate gender in the apparently wide range of things you are interested in?

KE Not in the center, definitely. Usually when gender is associated with my photos, female sensitivity is mentioned. Except for organizing the exhibition NECC, where I also presented a series, I have never dealt with standalone gender issues. I do not usually concentrate on this topic, but rather let my female instincts work. My pictures have been called she-photos, but this is not conceptually tangible. I saw awkward situations which made me upset, and later they return in my photos. For example in the one in which I made a montage of my baby and the happenings on October 23. Some pre-arranged photos also capture this type of moments, like the one showing a set table above which a scarecrow is watching as if in the role of a caring mother.